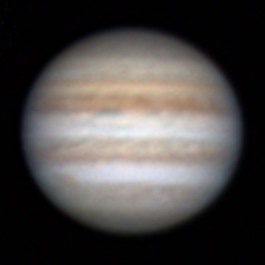

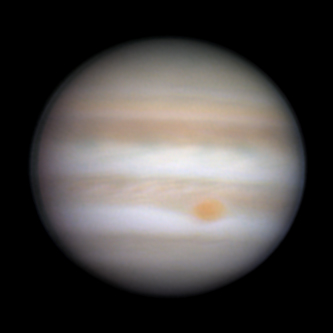

for a higher magnification jupiter

|

| Jupiter 5/28/17 |

meanwhile saturn reached opposition this week

coming up on prime viewing season

here's a wide field with a few moons:

|

| Saturn and Moons 5/14/17 |

|

| Saturn 6/14/17 |

will get to higher magnification when it rises earlier in the evening

Imaging notes:

The larger f/8 scope allowed me to use a 2x Barlow on jupiter, increasing the magnification by a factor of 2 compared to my old system (C8).

Several other issues were critical to getting the system to work:

1. internal thermal tube currents are a major problem with the new big scope, it takes hours to cool down. a "cat cooler" made a huge difference.

2. dark subtraction. this makes sense as i'm trying to minimize expsosure shooting at ~30% max histogram. the love/hate issue with my ASA DDM 60 mount continues. the issue here is that most mounts move around so much that the subtle grid pattern in the camera is dithered out. my mount tracks so well that the planet sits dead center even at very high magnification, so the pattern becomes evident in processing. this is actually a good problem to have. for example last night i took a series of images of jupiter at this focal length over the course of an hour and didn't have to budge the mount, even though the pointing model was made with a much lighter scope 6 months ago.

3. diagonal: didn't test that rigorously, but shooting through the diagonal didn't seem to make that much difference.

4. made a bit of progress working on LD compensation in win jupos which is necessary with jupiter so far from opposition, you can still see a darker section at the limb on the left (might be processing artifact in part).

5. more on the mount: the mount is very sensitive to weight changes, the act of switching from eyepiece to camera with barlow felt like this classic scene from raiders of the lost ark. the key is to balance the mount with the camera, not eyepiece. forget about binoviewers.

image details (jupiter):

Meade LX850 12" f/8

televue 2x Barlow

FocalLength~4100mm

Resolution~0.19"

ZWO ASI120MC/ASI120MM-S

ZWO RGB filters

4x2 minute captures for each filter R G B

captures with firecapture @ ~140 fps

exposure 3-4 ms per frame

stacked in autostakkert, combined in WinJupos, sharpened in registax 6

5/28/17 (2017-05-28-0446_7)

Eastbluff, CA