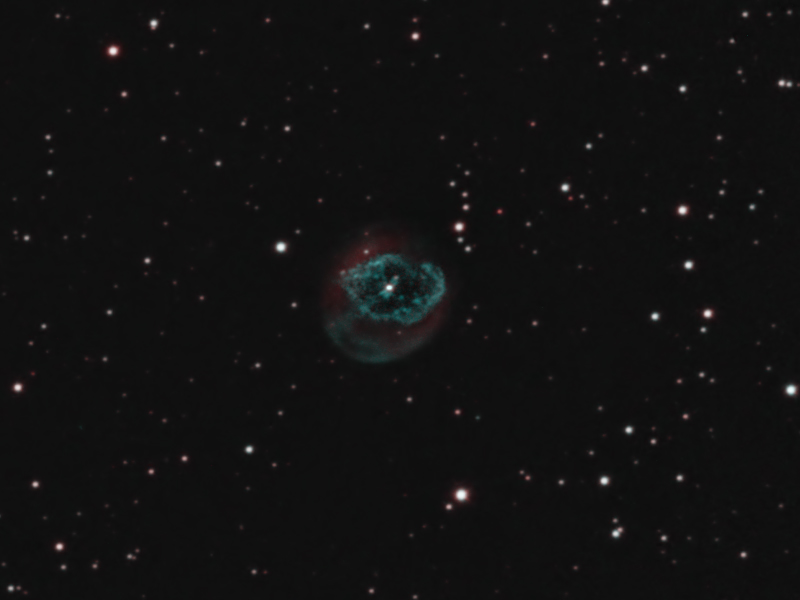

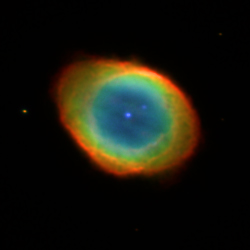

Sharpless-188 (SH2-188, Simeis 22 or the Dolphin Nebula) is one of the largest planetary nebulae known (9 light year diameter). Extremely faint, it lies in a relatively rich field in Cassiopeia, explaining the many pesky bright stars in the image. It's an excellent example of a planetary nebula interacting with the interstellar medium.

The tiny blue star to the right and just below the big orange star near the center of the arc is thought to be the central star/white dwarf.

It is is moving through the interstellar medium at 125 km/s (apparently really fast for such things). This creates a bright bow shock (upper right) and a faint streaming tail (lower left).

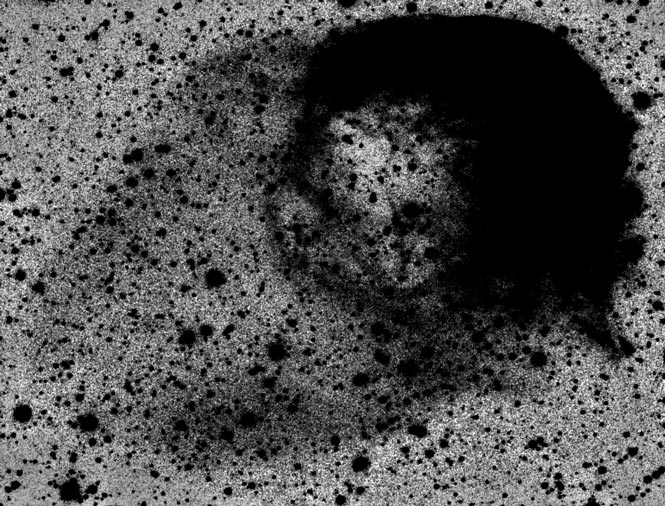

Here's an inverted image better showing the faint tail:

An interaction between the slow wind of the dying star, faster wind of the subsequent white dwarf, and rapid apparent wind due to motion through the interstellar medium is thought to account for the closing of the tail (arc connecting trailing lines of wake on either side, closing the ellipse).

More on this here:

The shaping of planetary nebula Sh2-188 through interaction with the interstellar medium

Wareing, C. J.; O'Brien, T. J.; Zijlstra, Albert A.; Kwitter, K. B.; Irwin, J.; Wright, N.; Greimel, R.; Drew, J. E.

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 366, 387–396 (2006)

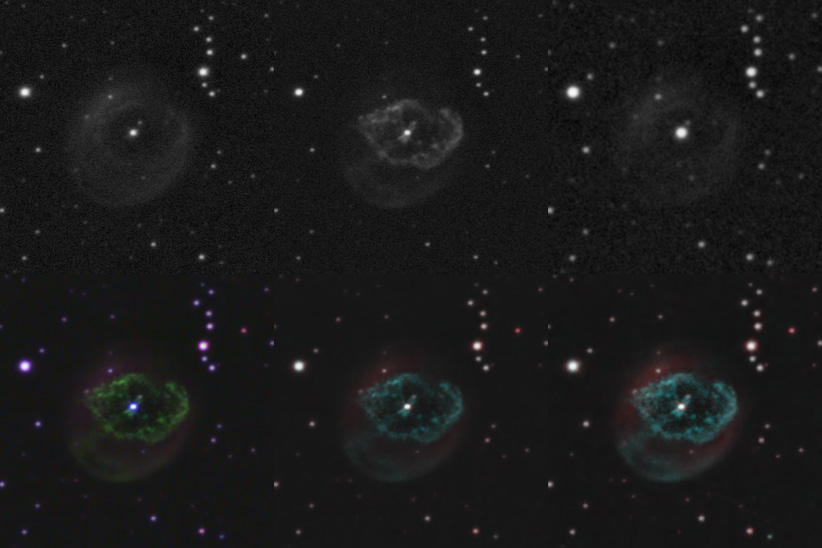

Here it is in Ha only:

Here's the OIII which didn't add much to the image:

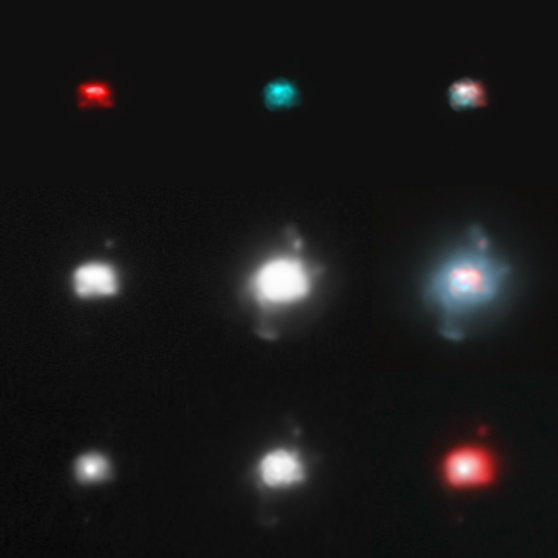

The faint tail was very difficult to capture, hence the exercise in faintness. Binning is a way to improving signal to noise ratio by combining groups of 4 pixels in the camera into one big pixel, giving 4 times the signal for the same amount of read noise. Here are two different images each consisting of 24 x 20 minutes exposures (8 hours). The first binned x2, the second binned x4.

Ha binned x2, then binned x2 again in software (no read noise advantage) to 4x:

Ha binned x4:

4x binning clearly does a better job distinguishing the faint tail from the background.

Really long winded rant on noise binning etc. (not for the faint of heart, really)

Background:

A digital camera has a chip which basically detects photons.

when a photon hits a pixel, it generates an electron*.

(* most of the time, my astronomical camera has a relatively high quantum efficiency of almost 80%, meaning 80% of the time a photon generates an electron)

At the end of the exposure, the register for each pixel is read and the measured potential is proportional to the number of photons hitting the pixel.

Things get quantum:

With very faint light, you start to see quantum effects in the images--a discrete variation in what should be a smooth area of a nebula.

The issue is actually worse than minor discrete differences from detection to detection.

When things get quantum, the detection of a signal has random variation which can be approximated by the square root of the signal.

Not a big deal for the bright core of a nebula which might give 40,000 photons per minute.

With a noise level of 200 for a one minute exposure, noise will represent only .5% of the detected value.

But with only 100 photons noise will represent 10% of the detected value.

Clearly with only 1 photon per minute, it's going to be very very difficult to separate the signal from the noise.

No problem, all we need to do is get more signal by increasing the exposure time...

most astronomical camera's are designed for very long exposure, with cooling to minimize the effect of thermal noise during long exposures (I run mine at -20C).

Formula, just for fun:

If N is the number of photons detected,

the inherent noise in the measurement will be sqrt(N)

and the signal to noise ratio will be N/sqrt(N) = sqrt(N).

So improving signal to noise is a bit of an up hill battle.

The cool thing about digital cameras is you can take one long exposure, or a series of short exposures and just add them up. By adding up exposures night after night, you can get a weeks worth of exposure time if you want.

Light pollution:

Here's why light pollution is such a huge problem.

Increasing exposure time increases signal, but also it increases the signal due to light pollution.

Suppose we have 1 photon per minute from a nebula and increase the exposure time to 20 minutes for 20 photons.

Light polluted skies can easily give you 2500 photons which gives an inherent noise level of 50,

So the

noise due to light pollution

exceeds the nebula

signal itself.

The skinny on narrow band filters:

But wait, all is not lost. For the case of an emission nebula, the signal typically consists of light at a single wavelength (or a few wavelengths). By using a narrow band filter which blocks all wavelengths but those that the nebula emits, the sky signal (which spans the entire spectrum) can easily be reduced by a factor of 100 (usually much more because light pollution is not uniform, for example there is a yellow peak due to sodium lamps).

Read noise:

Every time a digital camera takes a picture, there is a small amount of noise associated with reading the registers, typically on the order of a few electrons for a high-end astronomical camera.

Given the fact that there is noise generated by each exposure, a single long exposure, theoretically has less noise than a series of short exposures. The key to optimal exposure length is to make sure that the noise due to sky signal (light pollution in my case) far exceeds the read noise. If this is the case, the noise associated with a series of short exposures approaches that of a single long exposure. so sky noise can be your friend ;)

To bin or not to bin:

One issue that arises with narrow band filters is that the sky noise can be so completely suppressed that read noise becomes dominant, requiring extremely long exposures in order to efficiently stack a series of exposures. A problem I encountered with my new camera using ultra narrow band filters at long focal length was that the background signal due to light pollution was essentially reduced to 0 even with 20 minute exposures. Enter binning. Binning allows you to group 4 adjacent pixels together as one super pixel giving you 4 times the signal with the read noise of a single pixel. So you increase the ratio of signal to read noise at the expense of image resolution.

Proof is in the dolphin:

Theory's all well and good, but the question is: does binning make a difference?

For this extremely faint target I discovered binning x 4 does.

Lucky imaging in the near future:

Around the corner are cameras with zero read noise and near 100% quantum efficiency. These cameras allow stacking of extremely short exposures, potentially keeping only the lucky few captured during the best seeing.

8" LX200R, SX Trius 694 binned x2 to 0.8"/px, binned x4 to 1.6"/px

(final image at 1.6"/px)

astrodon 5nm Ha, 3nm OIII

ASA DDM60

Ha 24x20 min bx2, 30x20 min Bx4, OIII 29x20 min bx4

10/31-11/11/2015